The open, hoodoo-studded plains in the interior of the NORTHEAST CORNER OF SOUTH AFRICA are a patchwork of landscapes, with wetlands along the coast and surprising dense coniferous forests—a remnant of the colonial era when alien species were brought from Europe to create massive pine plantations. Underneath this variety lies one of the world’s biggest gold stores, and, underneath that, multiple miles underground, there’s a geographical fortune from profound time: layers of rock that give proof of Earth’s earliest profound freeze.

As per a paper distributed as of late in Geochemical Points of view Letters, these stones hold numerous signs to the world’s most established icy masses, sheets of ice that covered the region a shocking 2.9 a long time back. Now the major query is: Why was the ice there in the first place?

The longest-lived icy masses actually holding tight today are in Antarctica’s Dry Valleys, and are around 1,000,000 years of age — however a few specialists trust no less than one, covered under thick silt, might depend on 8,000,000 years of age. However, compared to the longevity of glaciers during the Huronian, also known as “Snowball Earth,” that old frozen water is but a drop in the bucket.

“Snowball Earth” has been applied to a couple of cold parts in the planet’s initial history (geologists love a snappy term as much as any other person). Be that as it may, the Huronian glaciation was, until the new South African disclosure, Earth’s most seasoned realized ice age — and it seriously took the cake. In general, the period endured in excess of 200 million years, starting around 2.45 quite a while back. While there were a few variances in environment during the Huronian, including generally warm and sticky periods, there were a few worldwide huge chills that endured 10 million years or more.

The revelation in South Africa, at field locales close to the line of Eswatini (previously Swaziland), uncovers Earth’s earliest ice sheets framed about a portion of a billion years before the Huronian. We have barely any familiarity with this period in Earth’s set of experiences; The planet was approximately 1.6 billion years old when the South African glaciers formed, and it was already home to microbial life forms, including some of the earliest multicellular organisms. However, it would take more than a billion years for more complex life to emerge.

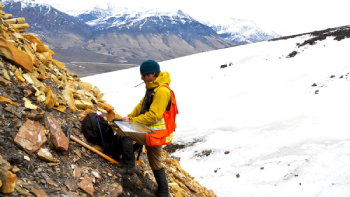

The specific geochemical signature of an icy climate was found by analyzing oxygen isotope levels trapped in rock strata in order to locate the oldest glaciers. They also found the world’s oldest known moraine, a distinctive pile of debris left behind when a glacier shrinks and expands.

The moraine and other proof have been saved for almost 3 billion years since they sit on the Kaapvaal craton, one of the most established enduring pieces of mainland hull. This old body of land, tracked down underneath a lot of South Africa, started conforming to 3.7 quite a while back and may have been important for Earth’s most memorable mainland, alongside Australia’s Pilbara craton.

Geologists enjoy debating the precise dates and locations of the first continent’s formation, and the data become less clear the further back in deep time we look. So does how we might interpret plate tectonics, the sluggish dance of landmasses across the planet’s surface. The coauthors of the new paper on the South African glacial masses accept the region where they found the old moraine might have been, structurally talking, near a pole and some portion of an ice cap before it slid to its ongoing spot north of millions of years.

In any case, there’s one more conceivable clarification for the super old glacial masses. They might be the main strong proof of a long and controversial lost ice age: the very first Snowball Earth, a planet-wide deep freeze that would have blanketed nearly the entire planet for at least a million winters.