According to a recent study, researchers in southwest England have discovered the planet’s oldest known fossilised woodland.

According to a press release from the University of Cambridge released on Thursday, the fossils, which date back 390 million years, surpass the record held by a forest in New York state by 4 million years.

The fossils were discovered next to a vacation park on the southern bank of the Bristol Channel, close to Minehead, in high sandstone cliffs.

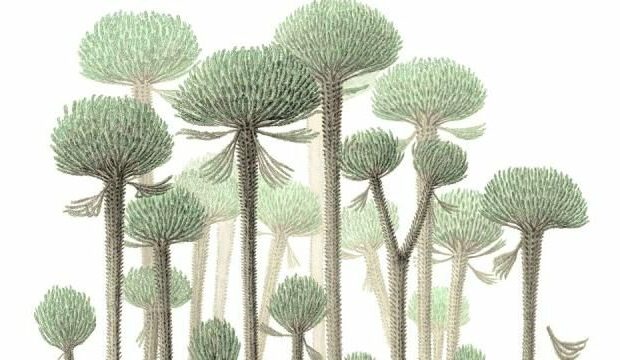

The trees, called Calamophyton, resemble palm trees in appearance, but their trunks are hollow and slender. According to research first author Neil Davies, a lecturer at the University of Cambridge’s Earth Sciences department, they possessed twig-like structures covering their branches instead of leaves, as he told CNN on Thursday.

As they developed, they would lose branches and grow to be as tall as 2-4 metres (6.6-13.1 ft).

The forest originated between 419 and 358 million years ago, during the Devonian Period, when life began to spread across land.

According to Davies, the trees would have stabilised riverbanks and beaches by retaining silt in their root systems.

He explained, “By doing this, they are creating these little channels and corralling water in specific areas.”“They’re basically building the environment they want to live in rather than being passive.”

According to Davies, the results also show how quickly early forests spread.

He clarified that although the fossils found in England are from a little forest that included only one kind of tree, the previous oldest forest in New York state had a greater diversity of species, including ground-dwelling vine-like trees, even though it existed only 4 million years later.

“By comparing the Somerset flora with the New York flora you really see how rapidly things changed in terms of geological time,” said Davies.

“Within a kind of geological blink of the eye you’ve got a lot more variety,” he continued.

Because the twigs would fall to the ground, the trees also offered a home for invertebrates that resided on the forest floor.

According to Davies, the scientists discovered proof of the early anthropods’ tail drags and footprints.

The biggest ones measured between 5 and 10 centimetres (2-4 inches) in width, although experts are unsure of their exact nature because there aren’t any physical remains, according to Davies. “They’re sizeable,” he continued.

In order to protect themselves from drying out in the extremely warm, semi-arid conditions, the team also discovered evidence that the arthropods would bury themselves in the silt on the forest floor, according to Davies.

The Hangman Sandstone Formation, the cliffs where the fossils were discovered, were then linked to areas of what are today Germany and Belgium, not England.

These locations have yielded comparable fossils from wood fragments washed out to sea, which have aided in the identification of the fossils discovered in England by research co-author Christopher Berry, a palaeobotanist at Cardiff University’s School of Earth and Environmental Sciences.

“It was amazing to see them so near to home. But the most revealing insight comes from seeing, for the first time, these trees in the positions where they grew,” he stated in the press statement.

“It is our first opportunity to look directly at the ecology of this earliest type of forest, to interpret the environment in which Calamophyton trees were growing, and to evaluate their impact on the sedimentary system.”

Without a tremendous amount of luck, none of this would have been conceivable, according to Davies.

“These were fortuitous findings,” he said, explaining that the crew had been in the region to look into the general geology and had been eating lunch in a field when they noticed the fossils.

“We were surprised to find the forest because it’s a part of the world that has been looked at quite extensively and no one’s ever found these things,” he remarked.

The study was released in the Geological Society Journal.