For a very long time, volcanoes have inspired fear, amazement, and wonder. The beating heart of our earth may be seen inside volcanoes, but those views are fleeting because volcanoes don’t give a damn about human cargo. This is devastatingly illustrated in the 2019 catastrophe film Ashfall, which is currently available for viewing on Peacock. The film centres on the eruption of the active volcano Paektu Mountain, which triggers a sequence of cataclysmic events along the border between China and North Korea.

The Korean peninsula is engulfed in chaos due to a mix of volcano eruptions and associated earthquakes, yet even our most terrifying natural disasters are nothing compared to the volcanic wasteland that is Jupiter’s moon Io (pronounced eye-oh). NASA is currently launching its Juno mission to investigate the solar system’s most volcanic planet.

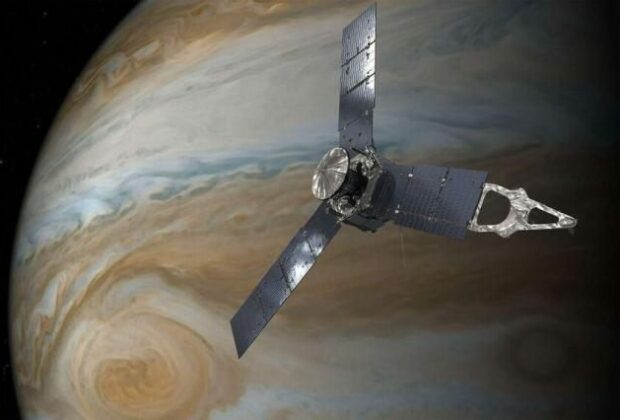

Getting Up Close and Personal with Jupiter’s Moon Io: NASA’s Juno Spacecraft

After launching on August 5, 2011, Juno travelled through interplanetary space for almost five years before arriving at Jupiter. On July 5, 2016, it entered the Jovian system, and ever since then, it has been zipping about the greatest gas giant in our system and its moons.

With its upcoming 57th flyby of Jupiter, which will bring the ceiling fan-shaped spacecraft closer to Io than it has been in more than 20 years, Juno will have completed 56 flybys of Jupiter in the last seven years. Io and several other moons of Jupiter have been surveyed by Juno during its mission, although always from a moderate distance—between 11,000 kilometres (6,830 miles) to 100,000 kilometres (62,100 miles). On December 30, 2023, Juno will descend to a height of only 1,500 kilometres (930 miles) above the surface of Io. On February 3, 2024, Juno will come past again, this time quite near and at around the same altitude.

According to a statement from Juno’s principal investigator Scott Bolton, “With our pair of close flybys in December and February, we will investigate the source of Io’s massive volcanic activity, whether a magma ocean exists underneath its crust, and the importance of tidal forces from Jupiter, which are relentlessly squeezing this tortured moon.”

All three of Juno’s imaging instruments—the JunoCam visible light imager, the Stellar Reference Unit, which aids in spacecraft positioning, and the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM), which records heat signatures from a planet or moon’s surface—will be operational and gathering data during those flybys. A tonne of information on the harsh environment on Io should be returned by Juno, shedding light on some of the extremes that exist not only in the cosmos as a whole but also in our own backyard.

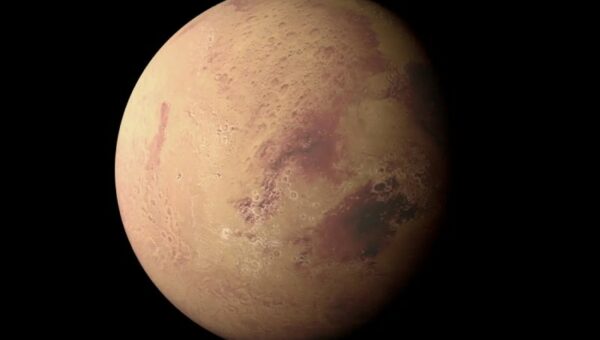

Volcanoes are scattered throughout the surface of Io, according to a Galileo probe photograph. The white patches on the right represent areas covered in sulphur dioxide frost, which is a gas that volcanoes release that soon freezes and rises to the surface.

Mission controllers had to modify Juno’s trajectory into a more advantageous orbit in order to get it into position, flying low over Io. This implies that for the duration of its extended mission, Juno will stay in orbit around Io. The spacecraft will continue to fly past Io on each following orbit after these two near passes. But that orbit will deteriorate rather quickly, pulling the spacecraft further and more from the Earth. When Juno makes the final of its eighteen passes over Io, it will be around 115,000 kilometres (71,450 miles) above the planet.