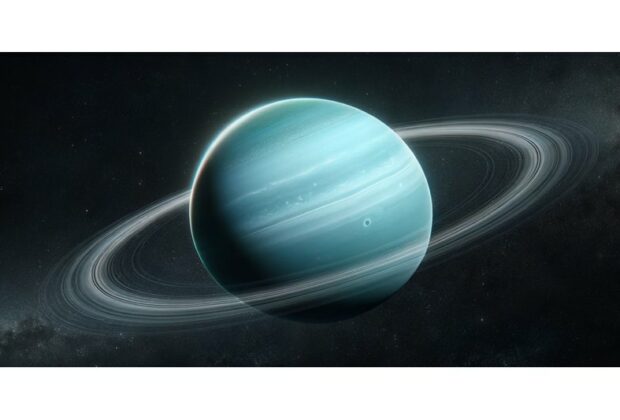

As the first and only spacecraft to reach Uranus, NASA’s Voyager 2 made history in 1986. Scientists gained a unique glimpse of the planet’s magnetic field from this close encounter, which led to some perplexing discoveries. But according to new research that was just published in Nature Astronomy, we might need to go back and review those conclusions.

According to the latest study, the planet’s magnetosphere may have been significantly distorted by high solar wind concentrations. According to the experts, this might have produced a unique situation during the flyby.As the first and only spacecraft to reach Uranus, NASA’s Voyager 2 made history in 1986. Scientists gained a unique glimpse of the planet’s magnetic field from this close encounter, which led to some perplexing discoveries. But according to new research that was just published in Nature Astronomy, we might need to go back and review those conclusions.

According to the latest study, the planet’s magnetosphere may have been significantly distorted by high solar wind concentrations. According to the experts, this might have produced a unique situation during the flyby.

Based on data from Voyager 2, Uranus appears to have a highly compacted and disordered magnetic field with severe radiation belts and plasma-free regions. But today, scientists think these harsh circumstances might have been an exception. Additionally, as Voyager 2 flew by Uranus, the magnetosphere might have been compressed by that solar wind.

Voyager 2 may have captured Uranus in a unique, heightened state because of the extreme “squeeze” that produced conditions that scientists estimate occur less than 5% of the time. It goes without saying that this solar wind would have changed what Voyager 2 could see.

It might have even distorted our perception of Uranus’s typical magnetosphere in certain respects. The magnetosphere of Uranus may not be as severe or erratic in a more normal state as the data from Voyager 2 suggested.

Scientists think that Voyager 2 would have found a calmer magnetic field and seen the planet substantially differently if it had arrived even a few days earlier or later. This discovery serves as a clear reminder of how dynamic the planets around us are, particularly when the solar wind is at work.

The magnetic fields of far-off planets like Uranus react to variations in solar wind pressure and solar storms in the same way that Earth’s does. However, our one flyby of Uranus only offered a fleeting glimpse under special circumstances that significantly distorted our conclusions about the magnetosphere, in contrast to Earth, where researchers may routinely detect these effects.

Future expeditions to Uranus are crucial in order to investigate the planet under various solar wind conditions, as the latest study further highlights. Scientists want to provide a more realistic picture of Uranus, including its odor, with a larger dataset.