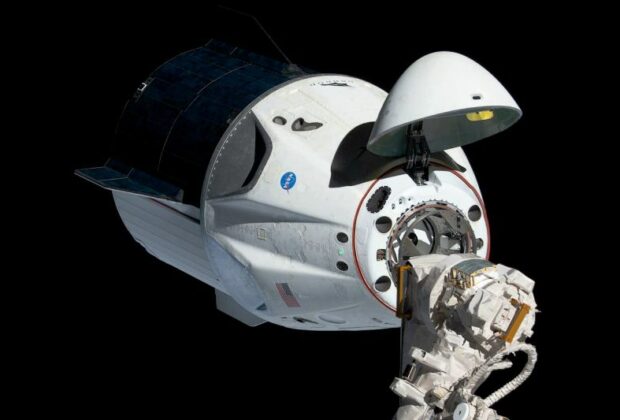

SpaceX announced on Wednesday that the $843 million spaceship it is developing to demolish the International Space Station by the end of the decade will be an upgraded Dragon capsule, similar to the one that is now used to carry people and goods into orbit.

Last month, NASA gave SpaceX a significant contract to create the U.S. Deorbit Vehicle (USDV). NASA stated in a source selection statement released on Tuesday that the design’s heavy reliance on flight-proven hardware helped it win the contract over Northrop Grumman, the only other bidder.

Dana Weigel, NASA’s ISS program manager, stated during a news briefing on Wednesday that the agency was searching for ideas that made the most use of flight heritage because dependability will be crucial. She said, however, that even with the substantial integration of the Dragon design, around half of the USDV and all of the de-orbit capabilities will be unique to this spacecraft.

Although NASA intends to launch the spacecraft about 18 months ahead of these burns, the USDV is intended to carry out a sequence of crucial burns that will occur during the final week of the station’s existence. According to Weigel, it will dock at the ISS’s forward port, where it will stay until the spacecraft gradually “drifts down” to Earth. The crew will stay on board for as long as necessary to keep the station on course, but six months or so before reentry, they will finally leave for good.

When the station reaches about 220 kilometers above Earth, the USDA will be activated. Before completing the last reentry burn, it will carry out a sequence of burns to position the station for an exact de-orbit trajectory over a period of about four days. The components of the station that survive the firestorm in Earth’s atmosphere will crash into an as-yet-unidentified area of uncharted ocean. The station has disposed of other large spacecraft, including Japan’s HTV cargo capsule and Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus, in a similar manner.

Due to the complexity of the mission, SpaceX will need to create a spacecraft that can maneuver the station through progressively greater atmospheric drag. “The thing that I think is most complex and challenging is that this [final] burn must be powerful enough to fly the entire space station, all the while resisting the torques and forces caused by increasing atmospheric drag on the space station to ensure that it ultimately terminates in the intended location,” said Sarah Walker, SpaceX’s director of Dragon mission management.

The final spaceship designed by SpaceX will have three to four times the power generating and storage capacity of Dragon capsules, along with six times the amount of useable propellant on board. The final product resembles a traditional Dragon with a large trunk affixed to its end, at least based on a render that SpaceX shared earlier on Wednesday.

Walker stated that the avionics, power generation, and additional propellant required to finish the trip will all be stored in that trunk. That adds thirty more Draco thrusters to the sixteen that are already present in the typical capsule arrangement. The goal of the enormous last burn is to minimize the amount of debris, which might include everything from small sedans to microwave ovens.

When NASA realized that Roscosmos’s capabilities weren’t sufficient for the size of the station, the agency collaborated with the other station partners, including the European Space Agency, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, the Canadian Space Agency, and Roscosmos, to request a deorbit vehicle from private industry. A request for proposals was issued by NASA last autumn.

Weigel stated that the reason the award is being given now is that developing a spacecraft this complicated can take years.

However, this deal differs from SpaceX’s previous significant wins for NASA. In contrast to its agreements with NASA for station crew and cargo transportation, wherein the space agency merely pays for SpaceX to own and operate the vehicles, the deorbit vehicle contract turns this on its head. While SpaceX will design and build the vehicle, NASA will be in charge of obtaining launch, managing the spacecraft, and actually returning the International Space Station to Earth.

In a separate solicitation, the government will begin the rocket procurement process around three years before launch. The International Space Station would splash down somewhere in 2030, assuming that activities end that year.

Officials from the agency expressed their desire to guarantee a smooth transition with commercial space station operators in low Earth orbit, but they acknowledged that several factors could cause obstacles. This contains the plans for the few commercial businesses that are currently developing stations, such as Axiom Space, Star-lab, which is led by Voyager Space, or Orbital Reef, a joint venture between Blue Origin and Sierra Space. NASA assistant administrator Ken Bowersox stated that after 2030, the agency would need to get permission from the government and collaborate with other space agencies in order to continue operating the station.